This week hundreds of policy researchers, implementation scientists, knowledge brokers, and donors gather in Prague to explore how to get research into action. Most of the Global Evidence Summit will be focused on research translation, building capacity for evidence informed decision making and the evaluation of evidence use. But in a quiet corner (hopefully not too quiet) of the poster presentation hall I’ll be sharing my experience of understanding scientists themselves and their alignment (or non-alignment) during emergencies.

This issue rose to prominence during the early stages of the Covid-19 pandemic, as public health advice appeared contested and scientists directly challenged one another and their government’s approach. This was at a time when hard data on a novel virus was in short supply and untried public health measures were being rolled out.

In 2021 I embarked on Doctoral research designed to identify epistemic networks and explore the factors, including proximity to government, that may shape these. This was in part driven by the accusation that emerged, that scientists working in close proximity to the UK Government during the first wave of Covid-19 were affected by a form of epistemological groupthink on issues like face mask usage in communities. I therefore decided to explore how scientists and public health experts’ insider to outsider status (their proximity to government) may have related to their alignment on policy advice.

My challenge was that rigorous analysis of social networks, such as who influences who, and network homophily (do birds of a feather really flock together?), rests largely on one’s ability to categorise members of the network correctly. If I wanted to test a hypothesis that scientists and public health experts’ insider to outsider status was a key attribute shaping their alignment, then I needed a way of determining everyone’s relative status. Who were the true insiders, or those in intermediary positions, or those operating as external advocates? I did not anticipate it being a simple binary choice between being in government and being an external advocate. I broke this challenge down into 5 analytical stages.

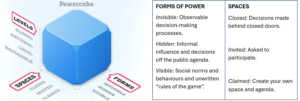

My research places great emphasis on the social and political structures that create core insiders and semi-insiders, who are the chosen few who are invited into closed spaces, and outsiders, who must claim their space. At one end of this spectrum I think of UK Chief Scientific Advisor, Patrick Vallance, standing shoulder to shoulder with Boris Johnson at Number 10 televised briefings. At the other end you may remember some of the prominent rebel academics tweeting their displeasure to their thousands of followers. For this, John Gaventa’s forms of power (invisible, hidden, visible) and spaces (claimed, invited and closed) is instructive. It helps us consider not just proximity to government but also hidden power (social norms and culture) and visibility in the public domain. Which of these types of power might we encounter when looking at scientists seeking to influence the use of evidence during a health emergency?

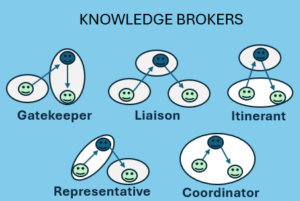

Network scientists Robert Fernandez and Roger Gould set out a hypothesis that suggests that converting structural position into power and influence is dependent on the type of brokerage position an actor occupies. It is important to distinguish between those who may claim independence from the state but play a gatekeeper role, versus those brokering knowledge on behalf of their own community and those who do not belong to either the group they seek to influence or the group they claim to represent. Their broker types, based on US health policy networks, give us five categories to choose from. This can help unpack precisely what role a science influencer plays on a spectrum of insider to outsider.

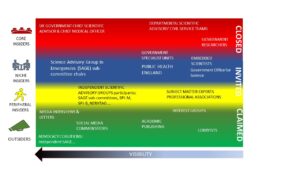

By combining these concepts of different forms of power and different brokerage positions I developed a framework for analysing the structural position of individuals and institutions in relation to the space they operate in. This quadrant makes plain the correlation between insider status and closed spaces but adds the additional dimension of visibility. You can see the power asymmetry emerge. However, I still needed to develop clear categories for my insiders to outsiders based on the complex science advice and influencing mechanisms in the UK in 2019-2020.

Political scientists have identified influencer roles ranging from: 1) Core insiders, 2) niche insiders, 3) peripheral insiders and 4) outsiders (Maloney, Jordan and McLaughlin, 1994). So, I took these and assigned them to specific groups or types of influencing that took place during the first wave of COVID-19 in the UK. I had to think carefully about the different forms of power (stage 1) and their brokerage role (stage 2).

For example, a scientist who chaired an independent scientific advisory sub-group and then attended meetings of the Science Advisory Group in Emergencies (SAGE) along with members of the Cabinet Office and the Chief Scientific Advisor, is closer to the government than members of the sub-group they represent. They are also playing a representative, or perhaps even liaison, broker role between university academics, who are unlikely to have direct access to senior decision makers and the government’s scientists. This places them in the Niche Insider category. Those simply coming along to some SAGE sub-committee meetings are also in an invited space but remain peripheral insiders.

Likewise, government scientists and public health experts (civil servants) are Core Insiders whereas the university academics they worked with directly who had been seconded into government departments are Niche Insiders. Our outsiders can be identified through a process of elimination. If you have no direct access to any of the official or informal structures that exist to engage evidence with government and so rely exclusively on publishing, social media and media interviews to make your voice heard, then you can be safely categorised as an outsider.

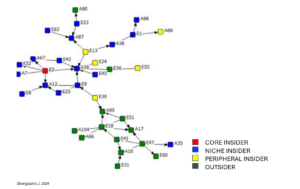

Although individuals will move between categories or occupy a fuzzy line between them, I used the typology that emerged from stages 1-4 to categorise every participant in my research. They were a broadly representative seed sample of 197 individuals who had agreed to participate, who spanned the whole range of functions set out above, from government scientists to science advocates in the media. I asked members of this network (survey and interview) for the names of scientists they had felt aligned with on the UK public health responses to the pandemic during the first wave, including school closures and face masks.]

UK scientists aligned on COVID-19 school closures policy (early to mid 2020)

You can adapt and apply this framework to any policy context, assuming you have access to enough data (the identities of science influencers). Your network can now be quantitatively analysed using empirical network analysis methods. For example, you can seek to test a hypothesis like mine by running network homophily scores for individual network members and whole networks. This compares the insider-outsider status of the respondents with their nominees and calculates the number of ties to different types of influencers minus matching ones, divided by the total number of ties, to give a homophily score ranging from perfect homophily to perfect heterophily. Assuming you have the data you can do this for any attribute you want such as sex, ethnicity, scientific discipline or age etc.

Spoiler alert – my own network data (research ongoing) shows relatively low levels of homophily overall, although there is a tendency towards stronger ties between those at the opposite ends of the spectrum of insiders to outsiders. This increases significantly where alignment relates to specific policy areas. Peripheral insiders demonstrate the highest levels of heterogeneity and appear to perform a cognitive bridging role that connects the core and niche insiders with outsiders. This makes them important actors in any science to policy network, even if they lack the relative visibility of some of their insider and outsider colleagues.

This blog is reposted from the Institute of Development Studies (IDS) News & Opinion section. James Georgalakis is IDS's Director of Evidence and Impact. Access James' Global Evidence Summit poster.

Find James @Bloggs74 or on LinkedIn.

Blog tile photo photo by Alina Grubnyak on Unsplash