In a collection of essays on storytelling, Philip Pullman argues that – unlike myths, or most fiction – science stories do not have an end. There’s no resolution; there are plenty of loose ends. They tell us how we got here, but “then they say, in effect, ‘The story continues, and the rest is up to you’.” Readers, he argues, are not told what to do or how to behave by science stories. Rather, while “the stories of science have moral consequences too…., they depend on our contribution, on our making the effort to understand and concur”. In other words, those who want to write their own science stories (for example, by participating in science), are morally obliged to make sure we know what the story is so far.

This struck me with unusual force. I have lately been musing on the tendency for those entering the study of evidence production and use to claim that they are forging a new, even "emerging" field. Often this plays out like this: scientists have discovered a problem; perhaps that many studies cannot be reproduced; perhaps that women are underrepresented in research as scientists and participants; or that they are struggling to get policymakers and decision-makers to pay them any attention. The scientists are excited – they have realised that many of these problems are to do with how research is done and used, rather than what is being researched. However, the next step for many is to assume that this is truly uncharted territory, rather than looking to see what stories have so far been told.

Nothing new about studying evidence production

In fact, of course, the funding, practices and outputs of scientific research have been the subject of research studies and indeed entire disciplines for decades, if not centuries. STS scholars, for example, debate what the role of science in society is, should be, or could be. The idea that this is a new endeavour would be surprising – possibly irritating, certainly disappointing – to those who study the history, politics and politicisation of science, the ethics and values of science and research, the interfaces between research and civil society, policy and the public; the ways, hows, and wherefores of how we allocate public resources to the production of evidence, and the ways in which evidence and knowledge shape and are shaped by public life.

This manifests as a proliferation of terms and theories – which isn’t necessarily a problem. Disciplines bring very valuable perspectives and methods to help us understand parts of the jigsaw puzzle.

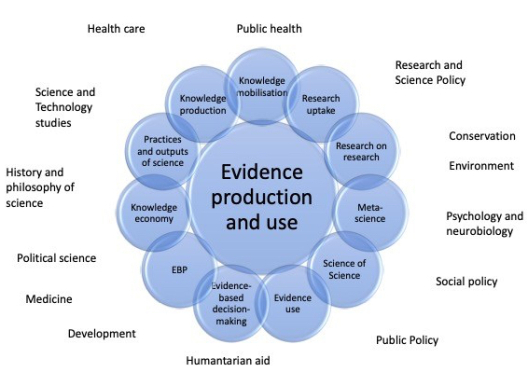

This manifests as a proliferation of terms and theories – which isn’t necessarily a problem. Disciplines bring very valuable perspectives and methods to help us understand parts of the jigsaw puzzle. For example, Nosek et al’s brilliant paper on the lack of reproducibility and significance across 100 social experiments, has clear implications, neatly captured by Bishop (2019) for those wanting to reduce research waste and flawed scientific studies. Similarly, implementation science, the “study of methods to promote the systematic uptake of research findings”, has provided a multitude of practical tools and theories to help people turn research findings into improved health care organisations and practices. In the, admittedly, unscientific diagram below, I’ve tried to sketch out how different disciplines talk about evidence production and use. These differences and nuances can be exciting and informative. But each have (usually quite clear) disciplinary homes to which they are tethered. Essentially, disciplines are having conversations with themselves about what they do.

Missing the big picture

The problem is the tendency to synecdoche; that is, the claim that the part of the puzzle they see is the whole picture – hence the proliferation of ‘new fields’ like meta-science, meta-research, research on research, science of science, and so on. One could easily dismiss this as mere "rebranding" – a trivial matter, simply a byproduct of the need to forge careers and get funding. But I think it really does matter. Every time a new term is coined, a new territory claimed, a new field declaimed, the message given out is – "This is new. No one has yet studied this. I do not, myself, know the story so far."

This is a terrible waste. Not only are we failing to learn from each other, we are saying that it is unimportant to do so. Too often time and resources are wasted on questions to which the answers are already known, or have been studied for decades. We are telling our collaborators that there are new, quick fixes to old, complex problems inherent in the relationship between evidence, policy and practice. For funders in particular, the promise of a transformative new approach that will maximise research impact can feel too good an opportunity to miss. As a consequence, opportunities for thinking and learning across disciplines to tackling thorny problems are repeatedly lost. We have to be honest about what this means for the quality of scholarship in this area.

We want to find a way to help different fields connect with each other more effectively around evidence use, to learn and research together and carve out a space for a wider debate to develop.

Reinventing the wheel

There are, of course, many understandable reasons why this situation has continued. Not least, that it’s quite hard to say to – often well-intentioned, brilliant – colleagues: “Look, this is a bit embarrassing but you’ve missed several decades-worth of research here”. Equally, most of us find it humiliating when we realise we’ve reinvented the wheel – I’ve often discovered my new insights are, well – not that new. And, for what it’s worth, I don’t think it’s fair or reasonable to expect individual researchers to learn about work in unfamiliar disciplines; overcome patchy and siloed funding for research in this area; struggle to build careers where there are limited opportunities for publication or discussion. But I think it’s a problem worth addressing. So, we want to find a way to help different fields connect with each other more effectively around evidence use, to learn and research together and carve out a space for a wider debate to develop. For me, this will take 3 main things:

For funders to recognize this as a cross-cutting area, and to support interdisciplinary and collaborative work in this area.Although all funders profess interest in maximizing the value of their investments, only a few take the study of evidence production and use seriously. In turn, this means that careers in this area cannot be built, so all who want to work on this problem have to do so as an ‘add-on’ or one-off to their ‘real’ research. Significant bodies of empirical and theoretical research are not easy to generate, and so where funders do invest, they often do so without an informed knowledge of the real knowledge gaps, leading to waste repetition and lack of progress. Those who choose to conduct relevant PhD research face challenges in continuing to pursue research in this area due to lack of funding opportunities.

Intellectual leadership

Relatedly, there is little time available for those who are working in this area to seek out their colleagues from other disciplines and domains. It takes job security and autonomy to be able to spend the significant time it takes to become fluent in research from multiple, disparate disciplines. Few have this time. And because of this, there is no recognised community to join and there has been limited leadership to help make connections.

Opportunity to listen and share knowledge. Most conferences and workshops (even where professing the opposite) are heavily skewed towards single disciplines or sectors. Time to meet and listen to each other, to learn the stories so far – this is an essential ingredient if we are really going to do new and interesting work in this area.

The Transforming Evidence collaboration has been established to try and help us to listen to each other’s stories, and write new ones together. We are talking to funders about investing in building the evidence base in this field, and how best to harness what we know already to support the use of their own investments. We are building platforms to share knowledge through Twitter, our calls for papers, and events. We would love to hear from you.

Kathryn Oliver is co-lead of Transforming Evidence and Associate Professor of Sociology and Public Health at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.