Written by:

Anna Hopkins

The idea that expert knowledge should inform government decision-making is almost as old as government itself, and in the present COVID-19 crisis it is taking place rapidly and in full public view.

European scholars often trace the image of the ‘public intellectual’ back to the dissenting philosophers of ancient Greece, although the perception and role of academics in public life has changed throughout history. Edward Said explored this in his 1993 Reith Lectures, which argued that it is the duty of intellectuals to represent and articulate important ideas for and to the public.

Over the last 50 years, effort and investment has gone into finding ways for government and legislatures to work with research organisations. The form these attempts take is evolving – as attitudes towards the role of evidence in policy shift; relationships between universities, industry and government are re-configured; and as academics grapple with some of the more naïve ideas about what their impact and influence should be.

At Transforming Evidence, we are piecing together an empirical picture of how interaction has changed over time, by building a database of organisations and initiatives that support government-academic engagement. Our first entry is logged in the 1920s and to date we have mapped the activities of 500 organisations operating over 30 countries. The research is ongoing but a story about how universities, policy bodies and many other organisations have sought to build links across policy and academia is coming together.

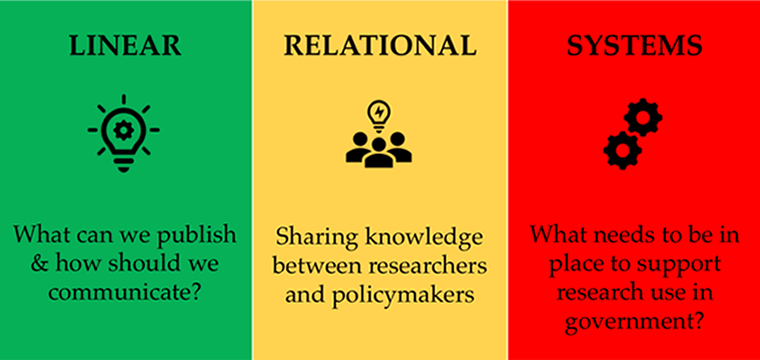

In Evidence and Policy in 2010, researchers Allan Best and Bev Holmes provided a framework for thinking about how perspectives on evidence use change over time. They argued there are three generations of thinking about how best to foster engagement, and that we move through these perspectives, cumulatively.

The first, which we focus on in this blog, is a linear perspective: it is characterised by a focus on dissemination, on knowledge as a product that can be straightforwardly applied to different contexts of use. Applying knowledge, and creating impact with research, is seen as a one-way exchange from people who produce research to those who use it. For the academic community, linear thinking on how to improve evidence use is plagued by the problematic image of Plato’s guardians – the ideal of experts acting as the protectors and counsellors of the public interest.

For the academic community, linear thinking on how to improve evidence use is plagued by the problematic image of Plato’s guardians – the ideal of experts acting as the protectors and counsellors of the public interest.

Investments in linear approaches

Linear approaches to improving engagement occupy the vast majority of the initiatives we have mapped, as well as a lion’s share of funding. Central to this approach is an emphasis on the importance of effective communication to ensure that research evidence lands with policy audiences and is used. From the late 1990s, sizeable investments are made by research funders and governments into ways of getting research findings out to different audiences.

The UK’s What Works Network has been at the centre of sharing and formalizing ideas about how best to communicate research since the 2010s. For some time, the evidence community has been thinking carefully about how best to communicate their ideas – we now have a growing knowledge base on what successful communication looks like, which emphasises, for example, the importance of tailoring messages to audiences and being aware of the messy processes and time sensitivity of politics.

Dissemination is a push mechanism for improving evidence use– it is driven by academic interests, researchers sharing what they learn with others. Pull mechanisms, by contrast, are driven by demand from knowledge ‘users’. Some pull mechanisms are among the most traditional ways that governments seek expert input – through Departmental Advisory Bodies and Expert Groups, responses to consultations, as well as via mechanisms like Select Committees. Others have emerged more recently. Beginning in the early 2000s, but picking up pace around 2015, we can trace the growth of initiatives that support policy to commission research more effectively, as well as co-create research or develop briefs through consultation.

One example of supporting government to commission research is the What Works Network’s Trial Advice Panel, set up in 2015 (and recently relaunched) to support departments and public bodies to evaluate services. Other examples include the US Research4Impact’s ‘matchmaking’ service, which pairs social scientists and policymakers; and the Sax Institute’s intelligent online tools that help Australian decisionmakers conduct research. The UK’s Policy Research Units represent a major investment from the National Institute of Health Research in informing longer-term policy development through close consultation with government.

Policymakers are not a “blank slate” on which science might impress the best course of action

The shift from push to pull approaches reflects some of the most important learning from what’s been tried so far. Policymakers are not a “blank slate” on which science might impress the best course of action (as the authors of this article argue). We now know that disseminating research is insufficient to improve use. We have established reliable evidence on presenting, communicating and improving access to research – but the relationship between policy and research is far more complex. Paywalled journals continue to limit access to research, and multiple social factors impact on how policymakers use academic research.

Addressing these challenges requires building on linear efforts to improve engagement between government and academia. It means recognising the complexity of policy processes, the social nature of evidence production and use, and the difficulty of transforming research and policy infrastructures. It also means coming to terms with a more realistic understanding of the role and limitations of expert knowledge in government.