Written by:

Jenni Owen

There is a growing body of research and guidance about how partnerships can bridge the disconnects between research and both practice and policy. Yet little attention has been given to the differences between practice and policy in the context of these partnerships. Jenni Owen reflects on the differences between types of ‘RPP’ and why these differences matter for impactful partnerships.

‘RPP’: does that mean research-practice partnership or research-policy partnership? The answer matters as it reflects likely differences between the roles of the partners, as well as the partnership’s context and structure. In this piece I explore some of these differences, drawing on my expertise and experience serving in the U.S. government three times (so far) and as Professor of Practice at Duke University’s Sanford School of Public Policy.

Before delving in to differences, it is useful to note two common similarities between research-practice and research-policy partnerships. They share the purpose of generating and using evidence to inform decision making and action. Both practice and policy partners often work in government organisations or organisations that use government (i.e. public) funds. With those overarching similarities in mind, we can turn to some key differences between research-practice and research-policy partnerships and why these differences matter.

Consider these two partnership scenarios:

There has been extensive documentation and study of the differences and disconnects between research and both practice and policy. Those differences help to explain why research-practice and research-policy partnerships are not more common and the challenges that they face. There is also a growing body of guidance about RPPs. However, little attention has been given to the differences between practice and policy in the context of research partnerships. Using the scenario above, this piece articulates a few key differences and provides some useful prompts for researchers and their partners to ask when embarking on a new partnership. Knowing the answers to these questions can help partnerships start strong and succeed. The piece concludes by outlining the potential of both types of partnerships to produce meaningful and lasting outcomes and impact.

The different roles of practice and policy partners

The roles of practice and policy partners have implications for research partnerships. Consider:

As this simple example highlights, whether the “P” partner is in a practice or policy role is directly tied to the production and use of the research. Research use matters for other aspects of the partnership too, including whether it achieves the goal of informing decision making and action.

[*The policy partner in a research-policy partnership is not limited to government agency representatives; they may also be elected officials.]

The different contexts for partner participation in RPPs

In the scenarios above, as in many RPPs, both practice (teacher) and policy (agency official) partners work in the public sector. Yet, the context for the partnerships differ in multiple ways. A few examples:

Again, in many RPPs, practice or policy partners are in government but in different government contexts. In the US, this includes different levels of government (local, state, federal), as well as branches (executive, legislative, judicial) – but the broader point is relevant elsewhere. Awareness and information about the context for any partnership can help provide a strong foundation for the partnership and its potential for informing practice or policy decisions and action.

Different structures for partnerships

The components of the research and the timeframe for conducting it are important aspects of any research partnership. Understanding how these aspects differ is important for partnership success.

Policy and practice partners both lament how long it can take for research to yield useful and useable evidence. While not the focus of this discussion, there are strategies for mitigating that challenge, including capitalising on the incremental learnings that occur throughout each partnership.

Positioning partnerships for success: five key questions

Identifying often-ignored differences between ‘RPPs’ can help to surface nuances about partnerships and enhance chances of success. While there are exceptions to the points outlined above, it is critical to consider partnership roles, context, and structure, whether from the perspective of a researcher, policymaker, or practitioner. To position partnerships for success, I suggest that researchers and their partners ask and answer the following questions when establishing partnerships, and have the answers in mind as the partnership unfolds.

For researchers, acknowledging the differences between partners within government and why they matter also highlights the importance of taking care when describing and studying RPPs, or providing guidance about them. The ‘P’ in play has implications for both theoretical and empirical work.

High potential for impact

Research-practice and research-policy partnerships are increasing world-wide, across disciplines, domains, levels and branches of government. When successful, they enhance research relevance, inform practice and policy, and can lead to the greater use of evidence for decision making and action. They can contribute to program and policy changes at the organisation and systems level. And, they can help bridge gaps between two sectors - research and government - that are traditionally isolated from each other.

Research-policy and research-practice partnerships have immense potential for meaningful, lasting impact. Understanding some of the common differences between them can contribute to making the most of the opportunities such partnerships provide. If you have been reflecting on the differences between types of ‘RPPs’ and why these matter, or if this piece has generated new thinking, I’m interested in hearing from you.

---

About the author

Jenni Owen is on the faculty of the Duke Sanford School of Public Policy where she focuses on government-research and government-philanthropy partnerships. She has served in government three different times and is co-editor of the book, Researcher-Policymaker Partnerships: Strategies for Launching and Sustaining Successful Collaborations. You can reach her on LinkedIn here.

---

Appendix. An example: The Finish Line Grants Program

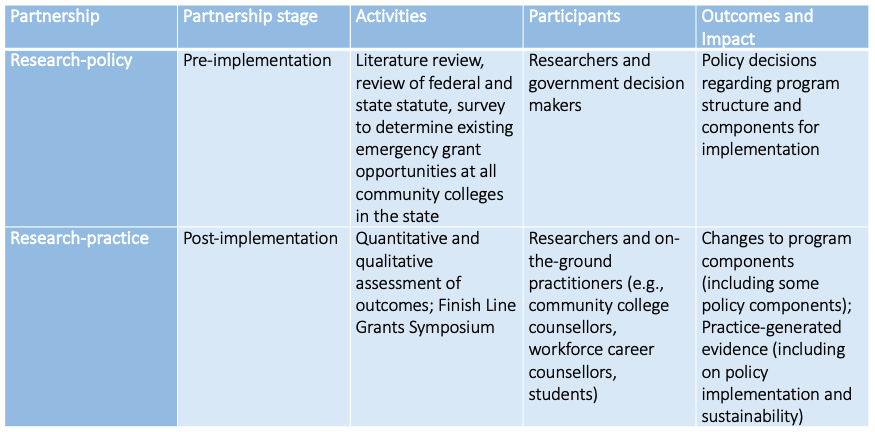

The Finish Line Grants Program illustrates some of the context, structure, participant, and outcomes differences between research-policy and research-practice partnerships.

A research-policy partnership helped to develop the Finish Line Grants program. Representatives from multiple state government agencies and researchers partnered to examine existing research and to conduct new research. The research had impacts on decisions related to the policy, leadership, structure, requirements, and other aspects of the new program.

A research-practice partnership followed implementation and helped to determine how well the program was working and potential improvements. The partners were researchers and the people working directly with community college students. While the first partnership focused on policy development, it still included the input of those who would be providing services to students. The post-implementation partnership focused on implementation and operation, the experiences of students and staff, and other practice-related program components.

As this example demonstrates, practitioners matter for policy. In the case of the Finish Line Grants Program, students and instructors featured prominently in the research that led to establishing FLG and to decisions made post-implementation; also, practice generated evidence, which affected policy.

Ideally, research-policy and research-practice partnerships inform each other. Practice partnerships have potential to directly and indirectly do some of the implementation and sustainability work that leads to policy partnerships.

Research-policy and research-practice partnerships for the Finish Line Grants program (overview for illustrative purposes, not comprehensive)