Written by:

Benjamin Hofmann

Manuel Fischer

Karin Ingold

Eva Lieberherr

Sabine Hoffmann

To contribute more effectively to the governance of major environmental problems, scholars need to build more systematically on prior insights by fostering well-functioning science-policy interfaces. We outline five opportunities for such knowledge cumulation – from democratic discourse to improved targeting of synthesis products.

In many research fields that analyse pressing problems of today’s societies, researchers lament their field’s small impact on policy. One such field is environmental governance. Decades of intense research and global network building, such as through the Earth System Governance Project, contrast with limited real-world progress in halting problems such as global warming and mass extinction.

One diagnosis about the limited impact of environmental governance research is that scholars have failed to “cumulate” knowledge in effective ways, i.e., to construct a coherent and interconnected body of knowledge. According to some scholars, researchers need to build their work more strongly on previous insights of their colleagues in terms of theories, methods, and empirics. More extensive knowledge use and synthesis within academia is a prerequisite for more evidence-informed decision-making. This thinking resembles the linear model of evidence use, where science needs to get better and push its findings more effectively in order to have greater impact.

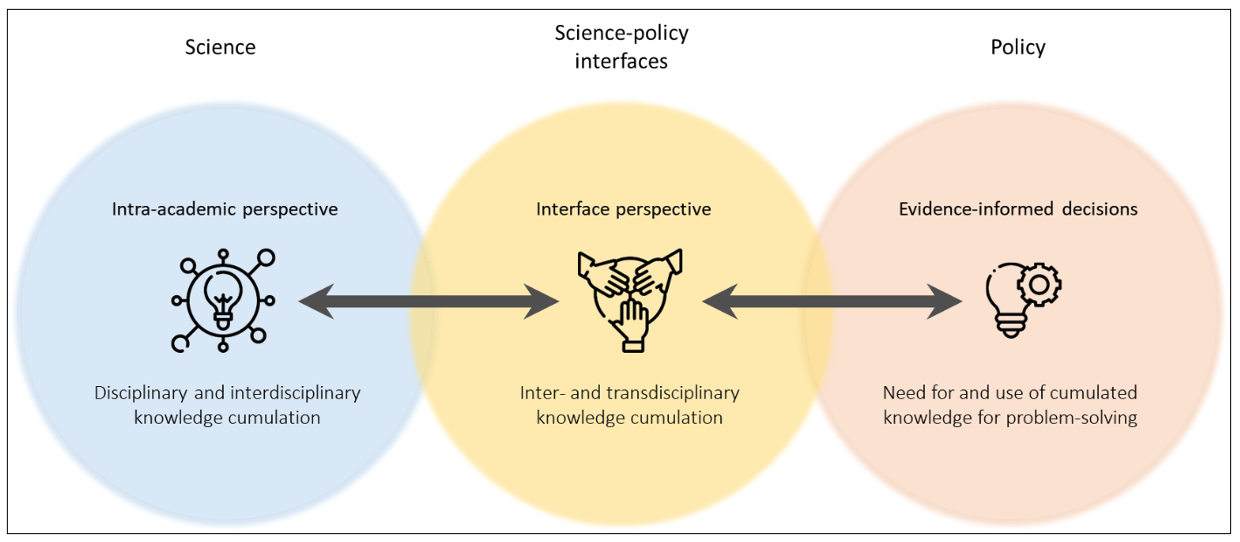

The diagnosis, however, is incomplete and the limitations of linear models of knowledge use are well-known. In addition to within academic sector, the interfaces of science and policy are themselves crucial for cumulating knowledge. Knowledge cumulation at these interfaces involves inter- and transdisciplinary knowledge integration and synthesis with a double focus on problems and solutions. It is one of the missing elements needed to connect scientific evidence production to evidence-informed policymaking. This interface perspective speaks to both relational and systemic models of knowledge use.

Figure 1: Science-policy interfaces are an important site for knowledge cumulation. Source: Hofmann et al. 2025.

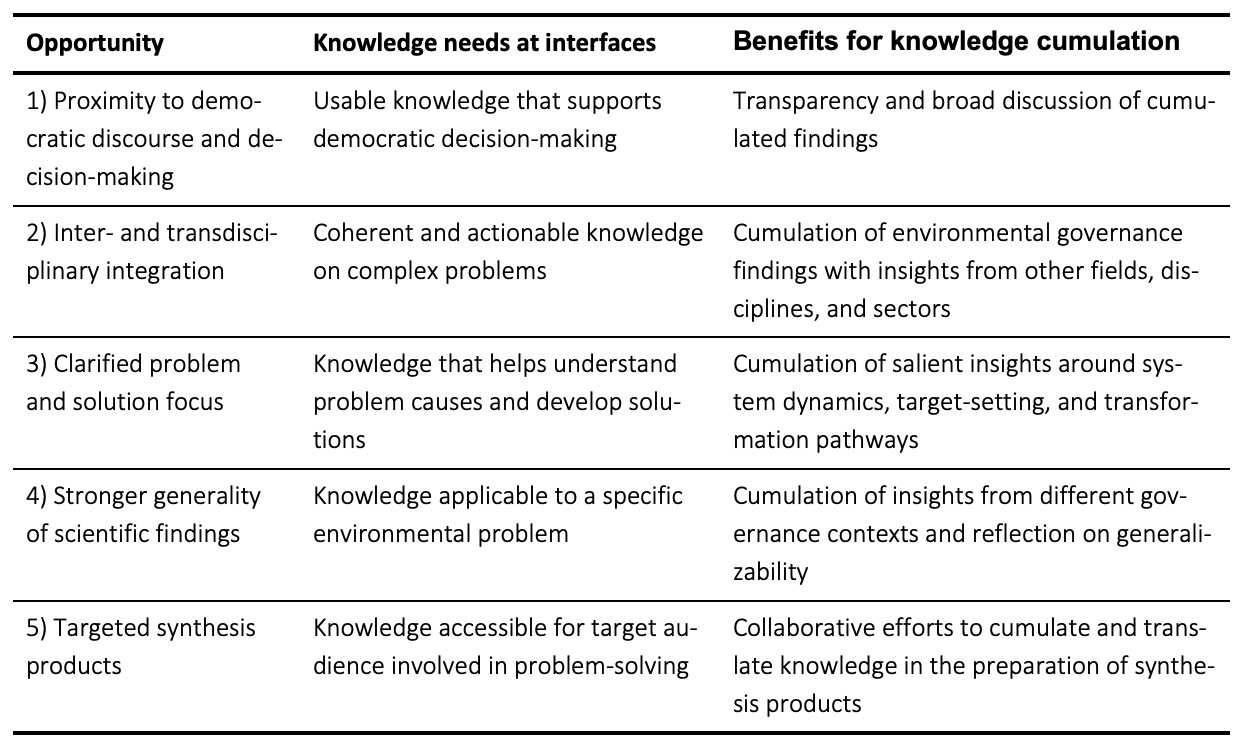

In a recent publication, we use examples of science-policy interfaces related to climate change, biodiversity, natural resources, and food systems to outline five opportunities for knowledge cumulation:

1) Increased proximity to democratic discourse and decision-making: Innovative forms of democratic decision-making, such as citizens’ assemblies, may support science-policy interfaces that cumulate knowledge about the deliberated problems. An example is the recent citizens’ assembly on future food policy in Switzerland. The nationwide assembly, funded by the Swiss government, developed a comprehensive set of policy recommendations based on advice from an interdisciplinary expert group.

2) Inter- and transdisciplinary integration: Effective science-policy interfaces should seek to provide coherent and actionable knowledge. This requires cumulation across scientific disciplines and with participation of stakeholders. To be effective, environmental policies need to fit the problem at hand and its geographical scale. Assessing problem fit in a holistic way relies on connecting the problem understandings of stakeholders to insights generated by natural and social scientists. An example of this is the SeaBOS initiative, which seeks to establish science-informed transnational sustainability standards in the global seafood industry.

3) Improved and clarified problem and solution focus: Scholars note that science-policy interfaces, such as global environmental assessments, increasingly move beyond an exclusive problem focus and engage with the solution space. This requires scientists to be clear about whether they cumulate system knowledge (what is), target knowledge (what should be), or transformation knowledge (how to move from the status quo to the desired future). One example is the global biodiversity panel IPBES, which uses diverse knowledge in its assessments. It has developed future pathways and scenarios, which can inspire more cumulative research, for example, on the effectiveness of different policy instruments.

4) Strengthened generality of scientific findings: Stakeholders often need knowledge on a problem context that lacks directly applicable research. Researchers and stakeholders are finding new ways to reflect on and share information about the generalisability of findings. One example is integrated river basin management in the Swiss multi-stakeholder platform Water Agenda 21. When contributing to such a platform, researchers studying a specific river have to explain why their findings are relevant to other basins in the country.

5) Targeted synthesis products: Science-policy interfaces often involve the co-production of synthesis products to provide accessible and relevant knowledge to stakeholders. An example is the Australian Centre for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis. It integrates data to co-develop solution-oriented publications and management recommendations that otherwise might not have been produced. By integrating knowledge and establishing joint datasets and models, synthesis products can lay the foundations for new lines of cumulative research.

Table 1: Five opportunities for knowledge cumulation at science-policy interfaces. Source: Based on Hofmann et al. 2025

Exploiting these five opportunities for knowledge cumulation at science-policy interface promises to contribute to both evidence-informed policy and scientific progress. It supports evidence-informed policy by providing a comprehensive and coherent body of knowledge that decision-makers can use to address complex problems in effective ways. It also supports scientific progress because cumulated knowledge prepares the ground for new research directions solidly anchored in the current state of the art and, at the same time, coupled to the knowledge needs of stakeholders. Thus, science-policy interfaces are not mere transmission belts for scientific information but can serve as two-way streets benefitting both academia and policymaking.

To take advantage of this potential, one crosscutting challenge must be addressed first. While many funders, research institutions, and governance stakeholders encourage researchers to engage at science-policy interfaces that cumulate knowledge, the rewards for such engagement remain limited. Working at these interfaces, researchers need to navigate roles that are more diverse and demanding and invest resources into outputs that feature less commonly in academic metrics of success. This requires proper training for and recognition of researchers’ engagement in science-policy interfaces that contribute to knowledge cumulation. These measures can complement the sound literature work, coherent theorizing, increased data sharing, and systematic empirical testing called for by the proponents of knowledge cumulation within academia. Thus, in our perspective, transforming evidence use in policymaking requires, as a precondition, transforming academic structures in ways that support researchers in cumulating knowledge not only within academia but also at interfaces.

Written by Benjamin Hofmann (Eawag: Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology), Manuel Fischer (Eawag/University of Bern), Karin Ingold (University of Bern/Eawag), Eva Lieberherr (ETH Zurich), and Sabine Hoffmann (Eawag/ETH Zurich Td Lab). The original study and the blogpost are part of the Sinergia projects TRAPEGO (“Evidence-based Transformation of Pesticide Governance”) and TREBRIDGE (“Transformation toward resilient ecosystems: Bridging natural and social sciences”) funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (CRSII5_193762, CRSII5_205912).